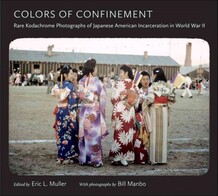

Last Friday I went to UMass Boston to attend a talk given by Professor Eric Muller, editor of Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in WWII which contains photographs by Japanese American internee, Bill Manbo. The talk was co-sponsored by the Institute for Asian American Studies (IAAS) and the New England Japanese American Citizens League.

I was surprised to find out about the IAAS. Although I've lived in Boston for years, I had no idea it existed. It was founded in 1993. They recently completed an interesting project called From Confinement to College: Video Oral Histories of Japanese American Students During WWI which "record[ed] first-hand accounts from Japanese Americans who were able to leave assembly centers and internment camps to attend college through the help of individuals or organization."

|

| Prof. Paul Watanabe, IAAS Director, introduces Prof. Eric Muller |

Bill Manbo and his family were incarcerated at the misleadingly named Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. [Note: President Roosevelt referred to Heart Mountain and the other 9 major camps as "concentration camps." Source: Eric's talk & Children of the Camps. It's only been in modern times that "concentration camp" has come to refer almost exclusively to the Nazi extermination camps. Some Japanese Americans think we should use concentration camp.] While there, he bought a camera -- something he would have done via a mail order catalog such as Sears Roebuck or Montgomery Ward -- and documented daily life. This was the first time I'd ever seen color photos of the incarceration and I don't really have the words to express how powerful they are. Scroll down for links to articles with photos.

For the photography geeks - the photos were actually slides and were taken with Kodachrome film. Eric said it was 6 years old in 1943, although Wikipedia indicates it would have been 8 years old. The slides were well preserved because they lived in Bill Manbo's closet for many years and then later his son's closet before being brought to Eric's attention by Bacon Sakatani, who was interned at Heart Mountain with the Manbos. Sixty-five of the 180 images made it into the book. Eric described the slides as having "barely seen the light of day" and said their disuse kept them beautiful.

You might be wondering how Bill could afford a camera and film. Being a US citizen, he would have had access to any funds he had put in his bank account prior to his incarceration and he also would have earned a government salary for working at the camp. Internees were paid $12/month for unskilled labor, $16/month for semi-skilled labor, and $19/month for skilled labor. [Source: Eric's talk & Japanese Americans at Manzanar] Heart Mountain was more or less run by the internees. At its peak, it was the third largest city in Wyoming after Casper and Cheyenne.

You also might be wondering how Bill Manbo was allowed to have a camera, which were originally contraband at all camps. Eric addressed this in his talk, but his answer from the UNC Press interview is more thorough so I'll quote from that. "Cameras remained contraband at the camps located within the military district called the Western Defense Command. But Wyoming was outside that zone, and by the spring of 1943, cameras were permitted. The WRA recognized that allowing internees to take pictures was a way of helping them reclaim some sense of a normal life and some of their dignity. "

|

| Eric shows us a black & white picture from the National Archives taken at Granada. |

Unfortunately, Bill passed away in 1992, long before this book project got started, and like many other older Japanese who were incarcerated, he didn't talk with his family about the experience. Eric told us that little is known about Bill Manbo's personality. He described Bill's son, Bill, (Billy when he was a boy), as a man of few words. Bill (senior) must have had a sense of humor - Eric mentioned that he had a French alter-ego, "Pierre Manbeaux." (You can see Manbeaux written on the porch he built on his family's barracks on p. 40.) My initial thought upon hearing this, was that he probably longed to be something other than Japanese. During WWII, Chinese people used to wear & post signs telling white people that they weren't Japanese, but rather Chinese. My Okinawan relatives were very proud of the fact that they weren't Japanese.

Something Eric said that I found particularly interesting was that in most Japanese American family albums there are pages missing for the incarceration years. Although Bill's photos were very personal to him, they really could have been taken at any camp and Eric sees them as representative of the missing pages in all Japanese American family albums. Most of Bill's photos are of his family and daily activities -- everything from Bon Odori and sumo to baseball and the Boy Scouts. Billy was a favorite subject and he's so cute and photogenic. Some of the images are so "normal" you wouldn't have any idea they were taken in a prison camp. But then, there are pictures like the one of the guard tower (one of 16 guard towers at Heart Mountain) on p. 45. It's similar to this photo. Eric says you can't mistake it for anything other than a photo about "surveillance and confinement." Then there's the photo from the back cover of Billy hanging on one of the barbed wire fences and the photo on p. 37 in which Billy looks utterly lost in the landscape with Heart Mountain looming in the background as he walks down a lonely road with the barracks and piles of coal to his left. It's clear that Bill was painfully aware of his and Billy's confinement. Eric commented "I don't take portraits of my kids like this." [Note on the fence photo: There were concentric circles of fences around the camp. When they first arrived, the fence that Billy is hanging on was the outer boundary of the camp, but in later years they eased restrictions and allowed internees to be in the outer ring during the day time, so Bill wasn't breaking the law when he took that photo.]

One of the most infuriating (to me and I'm sure many other Japanese Americans) things that happened during the incarceration was the administration of what's come to be known as The Loyalty Questionnaire (it was actually called DSS Form 304-A Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry). All incarcerated Japanese Americans had to fill out this questionnaire to prove their "loyalty" to the United States. Those deemed "disloyal" were packed off to Tule Lake where they shipped out the loyal and rounded up the disloyal. Bill and his wife, Mary, apparently had too many questionable answers so they were sent for hearings, although ultimately deemed "loyal." Eric located their questionnaires in the Archives and shared some of their answers with us. He said their anger practically leapt off the page.

Some of Bill's answers:

8. Citizenship of wife American?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization? If we get all our rights back [Note that this is clearly meant as a yes or no question, the line provided for your answer is very short. Eric mentioned that Bill's answers were off in the margins in some places.]

Some of Mary's answers:

8. Citizenship of husband US at present but I'm doubtful of it Race of husband Japanese, no fault of our own

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor , or any other foreign government, power or organization? Yes, I'm a born citizen

Some of Bill's answers:

8. Citizenship of wife American?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization? If we get all our rights back [Note that this is clearly meant as a yes or no question, the line provided for your answer is very short. Eric mentioned that Bill's answers were off in the margins in some places.]

Some of Mary's answers:

8. Citizenship of husband US at present but I'm doubtful of it Race of husband Japanese, no fault of our own

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor , or any other foreign government, power or organization? Yes, I'm a born citizen

Eric's talk was excellent and he was pleased with the turnout for a Friday afternoon. Lectures can be boring, even when the subject matter is compelling, if the lecturer just shows you a PowerPoint presentation and rattles off some fact and figures. Eric engaged the audience - asking us questions about what the images brought to mind and then providing background.

Colors of Confinement is not Eric's first book on the incarceration. He wrote two other books: Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters of World War II and American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II".

When I first read about Colors of Confinement and found out Eric has published other books about the incarceration I was wondering how a Caucasian law professor from North Carolina ends up researching the Japanese American incarceration. He said during the Q&A that he had a personal interest in American concentration camps because his grandfather was taken to Buchenwald. When I talked to him afterwards, he further explained that his first teaching job was actually at the University of Wyoming College of Law. He learned about Heart Mountain so he could bring it into the classroom.

Only some of the 65 photos from the book are available online. I highly recommend perusing a copy at your library or a bookstore if you can't afford the book. List is $35 although it's currently $23.10 at Amazon.

On a completely unrelated note, when I was flipping through the book and saw photos of the Boy Scouts, I found it really interesting that the Boy Scouts had the sense to allow Japanese American members at a time when we were considered so dangerous we had to be locked up, but they don't have the sense to allow LGBT members today (or athiests and agnostics for that matter).

More photos from Eric's talk.

Press on the book:

New York Times: Injustice, in Kodachrome - Slideshow

NPR: A Dark Chapter Of American History Captured In 'Colors'

UNC Press Blog: Interview: Eric L. Muller on new images of Japanese American internment in

World War II

Daily Mail: A secret diary of life inside America's WWII internment camps: Poignant photos show how Japanese-Americans ripped from their homes coped with confinement in California